The Poet at the Breakfast Table (1872) by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.

|

A collection of biographies

with surprising gaps (ex. A.D. Imms) |

The history of Indian interest in insects has been approached by many writers and there are several bits and pieces available in journals and various insights distributed across books. There are numerous ways of looking at how people viewed insects over time. One of these (cover picture on right) is a collection of biographies, some of which are uncited verbatim accounts from obituaries (and not even within quotation marks). This collation is by

B.R. Subba Rao who also provides a few historical threads to tie together the biographies. Keeping Indian expectations in view, both Subba Rao and the agricultural entomologist

M.A. Husain play to the crowd in their early histories. Husain wrote in pre-Independence times where there was a need for Indians to assert themselves before their colonial masters. They begin with mentions of insects in ancient Indian texts and as can be expected there are mentions of honey, shellac, bees, ants, and a few nuisance insects. Husain takes the fact that the term Satpada षट्पद or six-legs existed in the 1st century

Amarakosa to make the claim that Indians were far ahead of time because Latreille's Hexapoda, the supposed analogy, was proposed only in 1825. Such one-upmanship (or quests for past superiority in the face of current backwardness?) misses the fact that science is not just about terms but also about structures and one can only assume that these authors failed to find the development of such structures in the ancient texts that they examined.

Cedric Dover, with his part-Indian and British ancestry, interestingly, also notes the Sanskrit literature but declares that he is not competent enough to examine the subject carefully. The identification of species in old texts also leave one wondering about the accuracy of translations. For instance K.N. Dave translates a verse from the Atharva-veda and suggests an early date for knowledge on shellac. Dave's work has been re-examined by an entomologist, Mahdihassan. Another organism known in ancient texts as the

indragopa (Indra's cowherd)

supposedly appears after the rains. Some Sanskrit scholars have, remarkably enough, identified it, with a confidence that no coccidologist ever had, as

the cochineal insect (the species

Dactylopius coccus is South American!), while others identify it as a lac insect, a firefly(!) or as

Trombidium (red velvet mites) - the last for matching blood red colour mentioned in a text attributed to Susrutha. To be fair, ambiguities in translation are not limited to those dealing with Indian writing. Dikairon (Δικαιρον), supposedly a highly-valued and potent poison from India was mentioned in the work

Indika by Ctesias 398 - 397 BC. One writer said it was the droppings of a bird.

Valentine Ball thought it was derived from a scarab beetle. Jeffrey Lockwood claimed that it came from the rove beetles

Paederus sp. And finally a Spanish scholar states that all this was a gross misunderstanding and that Dikairon was not a poison, and - believe it or not - was a masticated mix of betel leaves, arecanut, and lime!

One gets a far more reliable idea of ancient knowledge and traditions from practitioners, forest dwellers, the traditional honey-harvesting tribes, and similar people that have been gathering materials such as shellac and beeswax. Unfortunately, many of these traditions and their practitioners are threatened by modern laws, economics, and cultural prejudice. These practitioners are being driven out of the forests where they live, and their knowledge was hardly ever captured in writing. The writers of the ancient Sanskrit texts were probably associated with temple-towns and other semi-urban clusters and it seems like the knowledge of forest dwellers was never considered merit-worthy by the book writing class of that period.

A more meaningful overview of entomology may be gained by reading and synthesizing a large number of historical bits, and there are a growing number of such pieces. A 1973 book published by the Annual Reviews Inc. should be of some interest. I have appended a selection of sources that are useful in piecing together a historic view of entomology in India. It helps however to have a broad skeleton on which to attach these bits and minutiae. Here, there are truly verbose and terminology-filled systems developed by historians of science (for example, see

ANT). I prefer an approach that is free of a jargon overload or the need to cite French intellectuals. The growth of entomology can be examined along three lines -

cataloguing - the collection of artefacts and the assignment of names,

communication and vocabulary-building - social actions involving the formation of groups of interested people who work together building common structure with the aid of fixing records in journals often managed beyond individual lifetimes by scholarly societies, and

pattern-finding a stage when hypotheses are made, and predictions tested. I like to think that anyone learning entomology also goes through these activities, often in this sequence. Professionalization makes it easier for people to get to the later stages. This process is aided by having comprehensive texts, keys, identification guides and manuals, systems of collections and curators. The skills involved in the production - ways to prepare specimens, observe, illustrate, or describe are often not captured by the books themselves and that is where institutions play (or ought to play) an important role.

Cataloguing

The cataloguing phase of knowledge gathering, especially of the (larger and more conspicuous) insect species of India grew rapidly thanks to the craze for natural history cabinets of the wealthy (made socially meritorious by the idea that appreciating the works of the

Creator was as good as attending church) in Britain and Europe and their ability to tap into networks of collectors working within the colonial enterprise. The cataloguing phase can be divided into the non-scientific cabinet-of-curiosity style especially followed before Darwin and the more scientific forms. The idea that insects could be preserved by drying and kept for reference by pinning,

[See Barnard 2018] the system of binomial names, the idea of designating type specimens that could be inspected by anyone describing new species, the system of priority in assigning names were some of the innovations and cultural rules created to aid cataloguing. These rules were enforced by scholarly societies, their members (which would later lead to such things as codes of nomenclature suggested by rule makers like

Strickland, now dealt with by committees that oversee the ICZN Code) and their journals. It would be wrong to assume that the cataloguing phase is purely historic and no longer needed. It is a phase that is constantly involved in the creation of new knowledge. Labels, catalogues, and referencing whether in science or librarianship are essential for all subsequent work to be discovered and are essential to science based on building on the work of others, climbing the shoulders of giants to see further. Cataloguing was probably what the physicists

derided as "stamp-collecting".

Communication and vocabulary building

The other phase involves social activities, the creation of specialist language, groups, and "culture". The methods and tools adopted by specialists also helps in producing associations and the identification of boundaries that could spawn new associations. The formation of groups of people based on interests is something that ethnographers and sociologists have examined in the context of science. Textbooks, taxonomic monographs, and major syntheses also help in building community - they make it possible for new entrants to rapidly move on to joining the earlier formed groups of experts. Whereas some of the early learned societies were spawned by people with wealth and leisure, some of the later societies have had other economic forces in their support.

Like species, interest groups too specialize and split to cover more specific niches, such as those that deal with applied areas such as agriculture, medicine, veterinary science and forensics. There can also be interest in behaviour, and evolution which, though having applications, are often do not find economic support.

Pattern finding

.jpg/737px-Eleanor_Anne_Ormerod_(1828-1901).jpg) |

Eleanor Ormerod, an unexpected influence

in the rise of economic entomology in India |

The pattern finding phase when reached allows a field to become professional - with paid services offered by practitioners. It is the phase in which science flexes its muscle, specialists gain social status, and are able to make livelihoods out of their interest. Lefroy (1904) cites

economic entomology in India as beginning with

E.C. Cotes [Cotes' career in entomology was cut short by his marriage to the famous Canadian journalist

Sara Duncan in 1889 and he shifted to writing] in the Indian Museum in 1888. But he surprisingly does not mention any earlier attempts, and one finds that

Edward Balfour, that encyclopaedic-surgeon of Madras collated a list of insect pests in 1887 and

drew inspiration from

Eleanor Ormerod who hints at the idea of getting government support, noting that it would cost very little given that she herself worked with no remuneration to provide a service for agriculture in England. Her letters were also forwarded to the Secretary of State for India and it is quite possible that Cotes' appointment was a direct result.

As can be imagined, economics, society, and the way science is supported

- royal patronage, family, state, "free markets", crowd-sourcing,

or mixes of these - impact the way an individual or a field progresses. Entomology was among the first fields of zoology that managed

to gain economic value with the possibility of paid employment.

David Lack, who later became an influential ornithologist, was wisely guided by his father to pursue

entomology as it was the only field of zoology with jobs. Lack however found his apprenticeship (in Germany, 1929!) involving

pinning specimens "extremely boring".

Indian reflections on the history of entomology

|

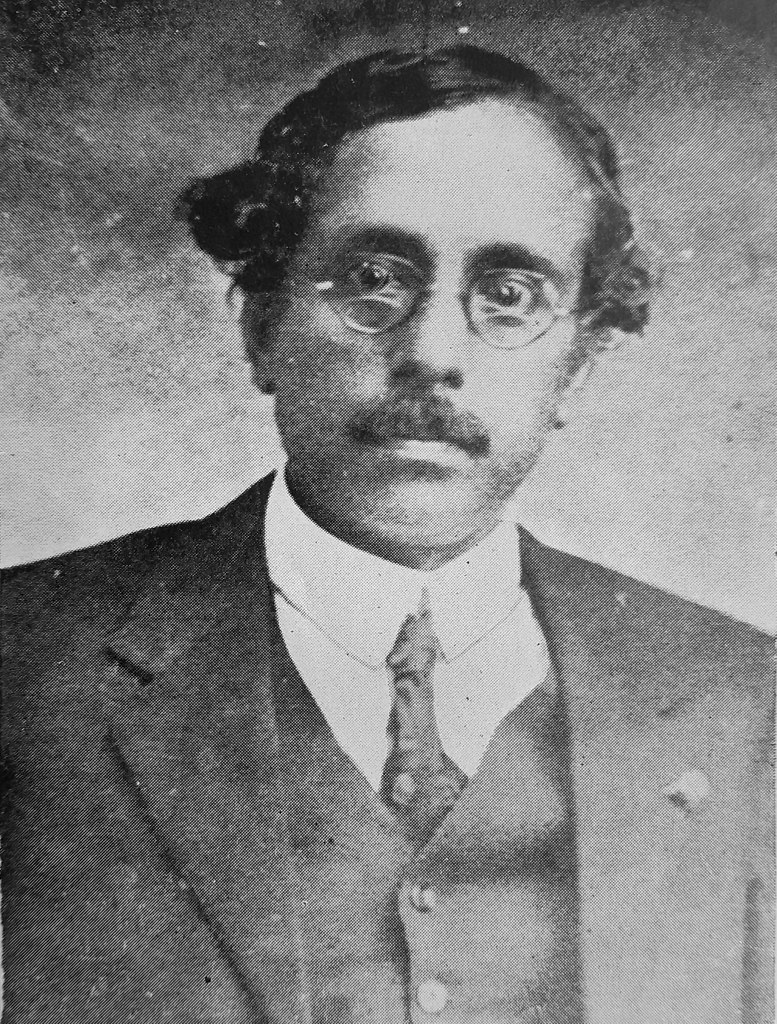

| Kunhikannan died at the rather young age of 47 |

A rather interesting analysis of Indian science is made by the first native Indian entomologist, with the official title of "entomologist" in the state of Mysore -

K. Kunhikannan. Kunhikannan was deputed to pursue a Ph.D. at Stanford (for some unknown reason two pre-Independence Indian entomologists trained in Stanford rather than England - see postscript) through his superior

Leslie Coleman. At Stanford, Kunhikannan gave a talk on Science in India. He noted in that 1923 talk :

In the field of natural sciences the Hindus did not make any progress.

The classifications of animals and plants are very crude. It seems to me

possible that this singular lack of interest in this branch of

knowledge was due to the love of animal life. It is difficult for

Westerners to realise how deep it is among Indians. The observant

traveller will come across people trailing sugar as they walk along

streets so that ants may have a supply, and there are priests in certain

sects who veil that face while reading sacred books that they may avoid

drawing in with their breath and killing any small unwary insects. [Note: Salim Ali expressed a similar view ]

He then examines science sponsored by state institutions, by universities and then by individuals. About the last he writes:

Though I deal with it last it is the first in importance. Under it has

to be included all the work done by individuals who are not in

Government employment or who being government servants devote their

leisure hours to science. A number of missionaries come under this

category. They have done considerable work mainly in the natural

sciences. There are also medical men who devote their leisure hours to

science. The discovery of the transmission of malaria was made not

during the course of Government work. These men have not received much

encouragement for research or reward for research, but they deserve the

highest praise., European officials in other walks of life have made

signal contributions to science. The fascinating volumes of E. H. Aitken

and Douglas Dewar are the result of observations made in the field of

natural history in the course of official duties. Men like these have

formed themselves into an association, and a journal is published by the

Bombay Natural History Association[sic], in which valuable observations are

recorded from time to time. That publication has been running for over a

quarter of a century, and its volumes are a mine of interesting

information with regard to the natural history of India.

This

then is a brief survey of the work done in India. As you will see it is

very little, regard being had to the extent of the country and the size

of her population. I have tried to explain why Indians' contribution is

as yet so little, how education has been defective and how opportunities

have been few. Men do not go after scientific research when reward is

so little and facilities so few. But there are those who will say that

science must be pursued for its own sake. That view is narrow and does

not take into account the origin and course of scientific research. Men

began to pursue science for the sake of material progress. The Arab

alchemists started chemistry in the hope of discovering a method of

making gold. So it has been all along and even now in the 20th century

the cry is often heard that scientific research is pursued with too

little regard for its immediate usefulness to man. The passion for

science for its own sake has developed largely as a result of the

enormous growth of each of the sciences beyond the grasp of individual

minds so that a division between pure and applied science has become

necessary. The charge therefore that Indians have failed to pursue

science for its own sake is not justified. Science flourishes where the

application of its results makes possible the advancement of the

individual and the community as a whole. It requires a leisured class

free from anxieties of obtaining livelihood or capable of appreciating

the value of scientific work. Such a class does not exist in India. The

leisured classes in India are not yet educated sufficiently to honour

scientific men.

It is interesting that leisure is noted as important for scientific advance.

Edward Balfour, also commented that Indians were "too close to subsistence to reflect accurately on their environment!" (apparently in

The Vydian and the Hakim, what do they know of medicine? (1875) which

unfortunately is not available online)

Kunhikannan may be among the few Indian scientists who dabbled in cultural history, and political theorizing. He wrote two rather interesting books

The West (1927) and

A Civilization at Bay (1931, posthumously published) which defended Indian cultural norms while also suggesting areas for reform. While reading these works one has to remind oneself that he was working under Europeans and may not have been able to discuss such topics with many Indians. An anonymous writer who penned a prefatory memoir of his life in his posthumously published book notes that he was reserved and had only a small number of people to talk to outside of his professional work. Kunhikannan came from the Thiyya community which initially preferred English rule to that of natives but changed their mind in later times. Kunhikannan's beliefs also appear to follow the same trend.

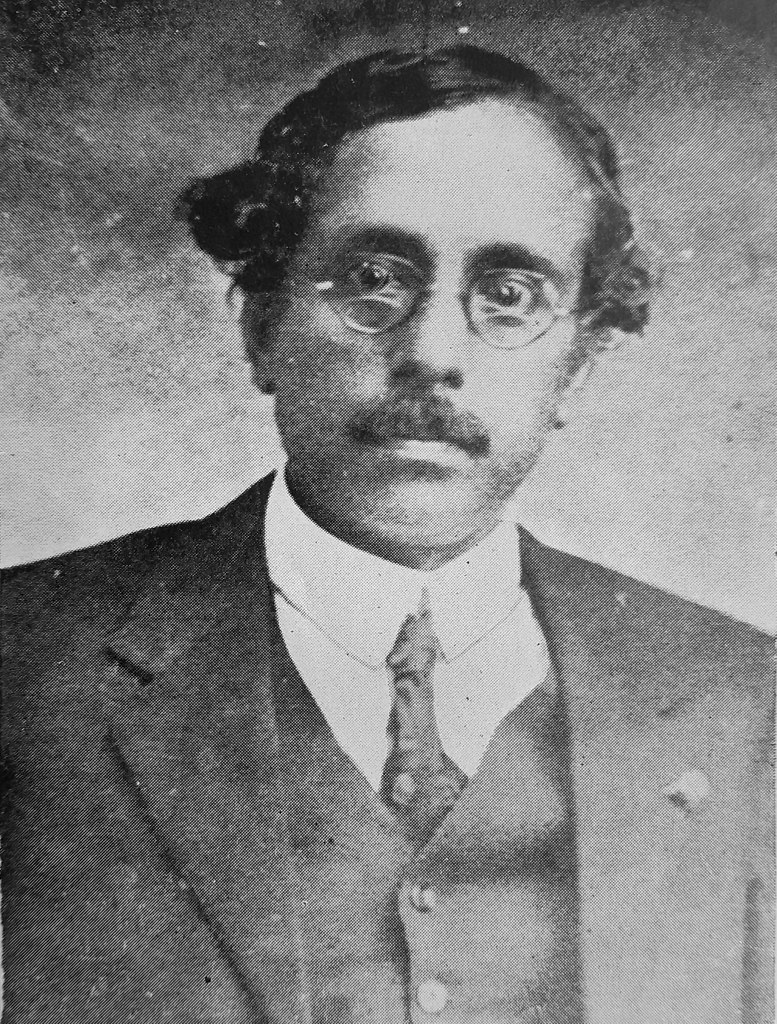

|

Entomologists meeting at Pusa in 1919

Third row: C.C. Ghosh (assistant entomologist), Ram Saran ("field man"), Gupta, P.V. Isaac, Y. Ramachandra Rao, Afzal Husain, Ojha, A. Haq

Second row: M. Zaharuddin, C.S. Misra, D. Naoroji, Harchand Singh,

G.R. Dutt (Personal Assistant to the Imperial Entomologist), E.S. David (Entomological Assistant, United Provinces), K. Kunhi Kannan, Ramrao S. Kasergode (Assistant Professor of Entomology, Poona), J.L.Khare (lecturer in entomology, Nagpur),

T.N. Jhaveri (assistant entomologist, Bombay), V.G.Deshpande, R. Madhavan Pillai (Entomological Assistant, Travancore), Patel, Ahmad Mujtaba (head fieldman), P.C. Sen

First row: Capt. Froilano de Mello, W Robertson-Brown (agricultural officer, NWFP), S.

Higginbotham, C.M. Inglis, C.F.C. Beeson, Dr Lewis Henry Gough (entomologist in Egypt), Bainbrigge Fletcher,

Charles A. Bentley (malariologist, Bengal), Senior-White, T.V. Rama Krishna Ayyar, C.M. Hutchinson,

E. A. Andrews, H.L.Dutt |

|

Entomologists meeting at Pusa in 1923

Fifth row (standing) Mukerjee, G.D.Ojha, Bashir, Torabaz Khan, D.P. Singh

Fourth row (standing) M.O.T. Iyengar (a malariologist), R.N. Singh, S. Sultan Ahmad, G.D. Misra, Sharma, Ahmad Mujtaba, Mohammad Shaffi

Third row (standing) Rao Sahib Y Rama Chandra Rao, D Naoroji, G.R.Dutt, Rai Bahadur C.S. Misra, SCJ Bennett (bacteriologist, Muktesar), P.V. Isaac, T.M. Timoney, Harchand Singh, S.K.Sen

First row (seated) Rai Sahib PN Das (veterinary department Orissa), B B Bose, Ram Saran, R.V. Pillai, M.B. Menon, V.R. Phadke (veterinary college, Bombay)

|

|

Note: As usual, these notes are spin-offs from researching and writing Wikipedia entries. It is remarkable that even some people in high offices, such as P.V. Isaac, the last Imperial Entomologist, grandfather of noted writer Arundhati Roy, are largely unknown (except as the near-fictional Pappachi in Roy's

God of Small Things)

Further reading

- Balfour, Edward (1887). The agricultural pests of India, and of eastern and southern Asia, vegetable and animal, injurious to man and his products. London: Bernard Quaritch.

- Ball, V. 1885. On the identification of the

animals and plants of India which were known to early Greek authors.

The Indian Antiquary. 14:274-287,

303-311,

334-341

- Barnard, Peter C. (2018). Bat-Fowlers, Pooters and Cyanide Jars: a Historical Overview of Insect Collecting and Preservation in MacGregor, A. (Ed.).

Naturalists in the Field

. Brill.

- Clark, J.F.M. (2001). Bugs in the System: Insects, Agricultural Science, and Professional Aspirations in Britain, 1890-1920. Agricultural History 75(1):83-114.

- Dave, K.N. (1950) Lac and the lac insect in the Atharva veda. Int Acad Ind Cult Nagpur, 16 pp. [Dave incidentally, is also the translator and interpreter of another problematic work on ornithological knowledge in ancient Indian literature]

- Dover, Cedric (1922) Entomology in India. The Calcutta Review 3(2):336-349. [Dover makes a plea for greater funding for entomology: Like Magda, Queen of Sheba, whose devotion to Learning made her set out for Jerusalem, the capital of the kingdom of Solomon, they have entered the domain of Science not with the object of any financial benefit to themselves but for their love of Knowledge. They have worked in the interests of Science alone, yet certain branches of their work has saved India millions of rupees, while other, have added large sums to her coffers. Is it not then up to the Government to improve the status of entomology in this country and to make it a more lucrative profession? ]

- Elias, Scott A. (2014) A Brief History of the Changing Occupations and Demographics of Coleopterists from the 18th Through the 20th Century. Journal of the History of Biology 47(2):213-242. [A nice examination of livelihoods]

- Essig, E.O. (1931) A history of entomology. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Farber, P.L. (1976). The type-concept in zoology during the first half

of the nineteenth century. Journal of the History of Biology

9(1):93–119.

- Hewitt, C. Gordon (1916). A review of applied entomology in the British Empire. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 9(1):1–33.

- Howard, L.O. (1930). A history of applied entomology (Somewhat Anecdotal). Smithsonian Institution. Publication 3065.

- Husain, Mohamad Afzal (1938). Entomology in India, past, present and future. Current Science 6(8):422-424. [This is a summary, for the full address see - Husain, M. Afzal (1939). "Entomology in India: Past, Present and Future." Proceedings of the Twenty-fifth Indian Science Congress, Calcutta, 1938. pp. 201–246]

- Lefroy, Maxwell (1904). Historical summary in Report of the Entomologist to the Government of India.

- Lienhard, S. (1978) On the meaning and use of the word indragopa. Indologica Taurinensia 6:177-188.

- Lockwood, J.A. (2012) Insects as weapons ofwar, terror, and torture. Annual Review of Entomology 57:205-227.

- Mahdihassan, S. (1986). Lac and its decolourization by orpiment as traced to Babylon. Indian Journal of History of Science 21(2):187-192.

- Melillo, E. D. (2013). Global Entomologies: Insects, Empires, and the “Synthetic Age” in World History. Past & Present, 223(1):233–270. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtt026

- Moses, S.T. (1925). Insect pests and some south Indian beliefs. Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society. 26(1):15-19.

- Rao, H. Srinivasa (1957) History of our knowledge of the Indian fauna through the ages. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 54:251-280.

- Rao, B.R. Subba (1983). Systematic entomology in India - past, present and future. Current Science 52(21):997-1000.

- Romero, D.B. (2007). El díkairon en la obra

Indika de Ctesias de Cnido. Propuesta de identificación. Emerita

75(2):255-272.

- Roy, Rohan Deb (2017). Malarial Subjects. Cambridge University Press. [Open-Access]

- Roy, Rohan Deb (2013). Quinine, mosquitoes and empire: reassembling malaria in British India, 1890–1910, South Asian History and Culture, 4(1):65-86. doi:10.1080/19472498.2012.750457

- Service, M. W. (1978). Review Article1: A Short History of Early Medical Entomology. Journal of Medical Entomology, 14(6):603–626. doi:10.1093/jmedent/14.6.603

- Smith, Ray F.; Mittler, T.E.; Smith, Carroll N. (1973). History of Entomology. Annual Reviews Inc. ISBN 0824321017.

- Sorensen, Conner (1988). The Rise of Government Sponsored Applied Entomology, 1840-1870. Agricultural History 62(2):98-115.

- Sutter, P. S. (2007). Nature’s Agents or Agents of Empire? Isis, 98(4):724–754.

An index to entomologists who worked in India or described a significant number of species from India - with links to Wikipedia (where possible - the gap in coverage of entomologists in general is large)

(woefully incomplete - feel free to let me know of additional candidates)

- C. Brooke Worth -

Kumar Krishna -

M.O.T. Iyengar -

K. Kunhikannan -

Cedric Dover

PS: Thanks to Prof C.A. Viraktamath, I became aware of a new book-

Gunathilagaraj, K.; Chitra, N.; Kuttalam, S.; Ramaraju, K. (2018).

Dr. T.V. Ramakrishna Ayyar: The Entomologist. Coimbatore: Tamil Nadu Agricultural University. - this suggests that TVRA went to Stanford at the suggestion of Kunhikannan.

.jpg/737px-Eleanor_Anne_Ormerod_(1828-1901).jpg)