God in his wisdom made the fly

And then forgot to tell us why.

- Ogden Nash

|

| Bengalia looking out for a victim |

One of my favourite flies was a species of Bengalia found especially during the rainy season. You will find him or her beside ant columns, watching stealthily and then making a quick dash and stealing a pupa or snatching food out of the mandibles of a passing worker. It was actually years between my first observation and finding the identity of the fly. The identity incidentally was made possible thanks to the Internet, on an email group, at a time when the web was still in its infancy. I posted a description of the behaviour and was entirely surprised when it was identified to genus by Dr D P Wijesinghe. Apparently the food-stealing or kleptoparasitic behaviour has been documented from early times. I later learnt that hardly anything is known about the life-history of this fly, which got me wondering how could anyone find more information about something like this. Perhaps one should build a large glass case and use some kind of passive marker with some detection apparatus on it to see where it goes. For all the spy gizmos and nano-technology, there does not seem to be any way. The only way to find out seems to be look out for it and to be prepared for surprise.

Lots of times, it is so hard to see what's happening. During the last rains I noticed a swarm of tiny silvery flies that seemed to like sunbeams under shaded trees. They are so alert and swift that they cannot even be captured. And no they are not hoverflies (Syrphidae). I asked my entomologist friends but they too have not figured a way to capture a specimen !

Another time I found this large aggregation of flies on a leaf. They have their forelegs raised and it looks a bit like a hand holding a sword. The structure is actually even closer to a pen-knife with a groove and the flies are actually capable of grasping prey - midges and indeed, the scientific name means midge-hunter. Now what this large aggregation is about is hard to tell, I suspect they are mostly males.

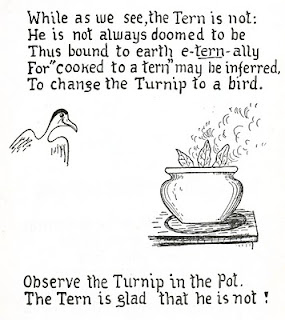

There are a couple of spectacular Internet gatherings of entomologists and the two that stand out at the moment are diptera.info and hymis.de - one on flies and the other on hymenoptera. These sites gather information, photographs and reassemble them into very interesting nuggets. They are the kind of system that brings together taxonomists, photographers and amateur entomologists. You can login, ask questions, obtain papers, identifications and so on. Today, I came across this entirely curious case of what can only be called "fly falconry" - check it out !

Postscript

- Found one paper with a technique for tracking live insects - Mascanzoni, D & H Wallin (1986) The harmonic radar: a new method of tracing insects in the field. Ecological Entomology 11(4):387–390 and a useful review but more of marking methods in- James R. Hagler, Charles G. Jackson (2001) Methods for marking insects: Current Techniques and Future Prospects. Annual Review of Entomology 46:511-543