On January 21, 1859 a bunch of subscribers to the journal The Field met at the London Tavern, Bishopsgate. At the head of the table was Richard Owen of Iguanodon fame and there was David W. Mitchell, artist and secretary of the Zoological Society of London and Francis "Frank" Buckland among others. Servings included a large pike, American partridges, a bean goose and meat from an African eland that had died at the Zoo. Several speeches were made after this exotic banquet, and the consensus was that one could have eland and game birds in the English countryside for everyone to hunt, eat and enjoy. Professor Owen later wrote in the newspapers on the delicacy of eland and the need for an "Acclimatisation Society".

|

| Luton Times and Advertiser - 29 January 1859 |

| |

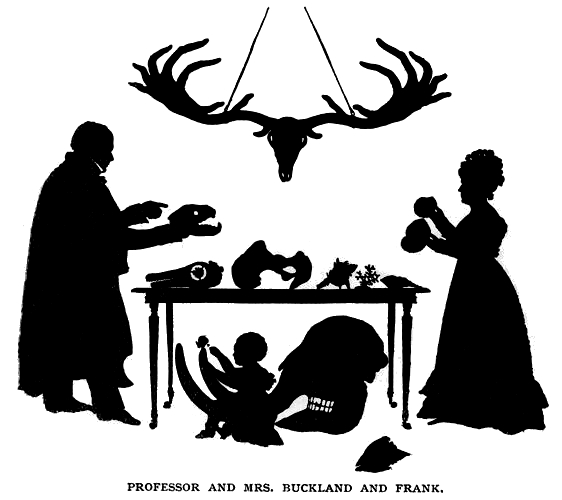

| Frank Buckland, the kid under the table. |

| ||

| Wattle expanding over the grasslands in Mukurthi (October 2013) |

The editors of the 11th edition of Encylopaedia Britannica apparently thought it fit that the entry on Acclimatization be written by Alfred Russel Wallace, and he spends considerable effort on a definition (v. 1:114-121 ):

The process of adaptation by which animals and plants are gradually rendered capable of surviving and flourishing in countries remote from their original habitats, or under meteorological conditions different from those which they have usually to endure, and at first injurious to them.An appendix to the entry is from Frank Finn of Calcutta:

The subject of acclimatization is very little understood, and some writers have even denied that it can ever take place. It is often confounded with domestication or with naturalization; but these are both very different phenomena. ... A naturalized animal or plant, on the other hand, must be able to withstand all the vicissitudes of the seasons in its new home, and it may therefore be thought that it must have become acclimatized. But in many, perhaps most cases of naturalization there is no evidence of a gradual adaptation to new conditions.

A great deal has been said about the upsetting of the balance of nature by naturalization, and as to the ill-doing of exotic forms. But certain considerations should be borne in mind in this connexion. In the first place, naturalization experiments fail at least as often as they succeed, and often quite inexplicably. Thus, the linnet and partridge have failed to establish themselves in New Zealand. This may ultimately throw some light on the disappearance of native forms; for these have at times declined without any assignable cause.

Secondly, native forms often disappear with the clearing off of the original forest or other vegetation, in which case their recession is to a certain extent unavoidable, and the fauna which has established itself in the presence of cultivation is needed to replace them.

Thirdly, the ill effect of introduced forms on existing ones may often be due rather to the spread of disease and parasites than to actual attack; thus, in Hawaii the native birds have been found suffering from a disease which attacks poultry. And the recession of the New Zealand earthworms and flies before exotic forms probably falls under this category. As man cannot easily avoid introducing parasites, and must keep domestic animals and till the land, a certain disturbance in aboriginal faunas is absolutely unavoidable. Under certain circumstances, however, the native animals may recover, for in some cases they even profit by man's advent, and at times themselves become pests, like the Kea parrot (Nestor notabilis), which attacks sheep in New Zealand, and the bobolink or rice-bird (Dolichonyx oryzivorus) in North America. Finally, it should never be forgotten that the worst enemies of declining forms have been collectors who have not given these species the chance of recovering themselves.

| |

| Hampshire Advertiser 1 August 1863, p. 3 The Bombay Cynthia is a silk moth |

One of the members of the British Acclimatisation Society was Robert Maitland Brereton, a railway engineer posted briefly in Nasik, central India. He promised to obtain some Indian game birds and deer. Viscount Powerscourt offered to get junglefowl and seeds of useful plants from Mysore. Edward Blyth also made offers but it appears that he was more interested in money. H.E. Watts wrote in 1864 of the pre-eminence of India as a sourcing area for introduction into Australia. He made a list of the best game birds to introduce that included the snow-partridge (Tetraogallus himalayensis) "five times the size of the common English bird, and of most exquisite flavour". As late as 1960, this species was trapped in Pakistan and introduced into the Ruby mountains in Nevada, USA where they still persist in the wild.

The work of the Australian acclimatisation societies involved introducing the skylark, blackbird, starling, chaffinch, Java sparrow and Indian myna! There were wealthy individuals like Eugene Schieffelin who made it his life's mission to introduce all the birds mentioned in Shakespeare into the United States of America. They still suffer from the starlings he introduced in 1890.

Notes

Francis Day was also a Hume collaborator, especially active during the Sindh expedition of 1871. Day's work in fisheries required him to work with the Department of Revenue, Agriculture, and Commerce where Hume was a secretary (1871-79).

There is apparently a book (that I have not seen) on the history of acclimatisation societies -

- Lever, C. 1992. They dined on eland: the story of the acclimatisation societies. Quiller, London

Postscript

Recent surveys have not found brown trout in southern India, suggesting that the species has been eliminated.

December 6, 2016:A 1977 publication by the Nilgiri Wildlife Association - here notes the following introductions:

Recent surveys have not found brown trout in southern India, suggesting that the species has been eliminated.

- K. V. Radhakrishnan, B. M. Kurup, B. R. Murphy and S.-G. Xie (2012) Status of alien fish species in the Western Ghats (India) as revealed from 2000–2004 surveys and literature analyses. J. Applied Ichthyology 28:778-784.

December 6, 2016:A 1977 publication by the Nilgiri Wildlife Association - here notes the following introductions:

- Acacia melanoxylon and A. dealbata were introduced around 1832 by Captain Dun

- Eucalyptus globulus was introduced in 1843 by Captain Cotton of the Madras Engineers (probably from Tasmania)

- Chukor partridge were imported and released in 1892 and again in 1910 and 1916 in the Nilgiris

- See-see Partridge were released in 1911 and 1916

- Red Jungle Fowl were bred in captivity and released but fortunately failed to live in the wild.

- Rabbits were introduced around 1892!

Harold Littledale (a professor English at Baroda, who married the daughter of one of the founding Indian members of the BNHS, Atmaram Padurang - causing perhaps much sorrow to Rabindranath Tagore) one of the early members of the BNHS proposed in 1890 that Markhor could be introduced into the Nilgiris.

References

- Carruthers, J., L. Robin, J. P. Hattingh, C. A. Kull, H. Rangan, and B. W. van Wilgen (2011) A native at home and abroad: the history, politics, ethics and aesthetics of Acacia. Diversity and Distributions 17 (5):810-821.

- Collins, Timothy (2003) From Anatomy to Zoophagy: A Biographical Note on Frank Buckland. Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society 55:91-109.

- Doughty, Robin (1996) Not a Koala in Sight: Promotion and Spread of Eucalyptus. Cultural Geographies 3:200-214.

- Whitehead, P.J.P. & P.K. Talwar, 1976. Francis Day (1829–1889) and his collections of Indian Fishes. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Historical Series 5(1): 1–189.

- Littledale, H. (1890). "Proposed introduction of the Black Partridge and other game into the neighbourhood of Bombay". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 5 (4): 417.

_Taurotragus_oryx_livingstonii.png)

_-_Male_-_Sakleshpur_-_India_-2009.jpg)