"... the terrible and wonderful ag-gadi, the fire-horse" - Edwin Arnold

Travel may be enjoyable, and adventure exciting, but it leaves behind a wake of destruction. With a growing appetite for fast cars and straight, sterile, high-speed roads, India is headed for assured destruction. In the shadows of this need for speed, those of us who have enjoyed and appreciated the wealth of wild India will have enough reasons to worry about the future. Reading about the past can either be an escape or a warning. The romance of India which attracted hordes of visitors was its wildness. Wild India's attraction, its visitors and rulers helped fuel its destruction.

| ||

| India from an early sailing perspective was just a slim peninsula Calecut Nuova Tavola by Girolamo Ruscelli, 1561 |

Getting from Europe to the exciting riches of India was not easy. The early sailships needed six to nine months and this was gradually reduced with the invention of paddle steamers, screw propeller and the construction of the Suez Canal.

|

| Rough seas and uncertain journeys (East Indiaman by Charles Brookings, cartoon by G. Cruikshank) |

Teak was found to be particularly good for marine use. Apparently you cannot use iron nails in oak (not for long at least) but teak was just great. English oak had been over-exploited[Albion 1926] and by 1795 the decision was made that "Country-built" (=Indian) ships be used by the East India Company.[Chatterton 1914:171] Shipbuilding took its toll on the forests of India but good wood does not give you a fast journey. Steam ships needed coal but ships from England could only carry a limited amount on board and coal was needed by the hundreds of tons for just a single voyage.

The railways in India were born to harvest the coal from the hinterland of India. As if that was not bad enough, the construction of tracks needed impossible amounts of strong timber for the sleepers and the steam engines needed firewood in addition to the coal that they needed to carry from the few places in the heartland to the ports where steamships waited. In the wake of all this destruction there were some influences on the study of India's fauna and flora.

The quest for coal, which enabled faster shipping from Britain to India, became particularly urgent after 1857. The slow sailships had also had their influence on the study of natural history, for the painful and often unhealthy journey required ship surgeons who were trained to appreciate the variations in the fauna of other lands and the medical value of flora. The need for speed, steamships hungry for coal (that had to stashed on St. Helena for reasons of economy and that island had been stripped of its wood, something that would catalyze other debates on the environment) brought in a slew of geologists, many Irishmen and one especially interesting Moravian. The geologists were trained to appreciate the past history of the earth, the signs of past life and coal, the result of long-gone vegetation.

|

| Early plans for the railways to harvest the coal and cotton bounty |

Valentine Ball, F.R. Mallet and Ferdinand Stoliczka were especially interested in natural history, all three were correspondents of A.O.Hume and collected bird specimens. Ball was also responsible for identifying the best route for laying the railway links between the Delhi-Calcutta rail line and the Bombay lines.

It did not take long to discover that the amount of wood needed for sleepers for the railways could simply not be met by the available forests. And there enters the story of Hugh Cleghorn and the idea of forest departments and commercial forestry.

A major "railways ornithologist" and Hume correspondent was W. E. Brooks who was early to recognize the importance of bird song in species recognition. A great friend of Hume, he named his son, Allan Brooks, the great Canadian bird artist after him. Another ornithological collector, George Reid of Lucknow, also worked in the Railways.

The railway infrastructure crisscrossing the country could not avoid an impact with other denizens. An impact in which the wild would most certainly lose despite the fact that it did not involve wanton killing as with the buffalo in North America. The stories of wildlife conflict only made India more exciting and enticing. The newspaper articles were sensational.

And it was not just encounters but death for many animals whose stories have never been told.

"The mail train between Madras and Bangalore ran down and killed a full-grown panther on a recent journey. Terrified at the approach of the train, the beast ran in front until exhausted, when it turned, and, viciously leaping at the front of the engine, was dashed to pieces."- Thursday 30 April 1903, Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, Devon, England

|

| A king cobra guillotined by a train on the Castle Rock line (November 2012) |

Despite all this the railway system is a much better (see http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.07.015) transport system than roads which probably have a far greater impact, apart from killing more people and burning up more fossil fuel.

Here is however some beautiful prose by Sir Edwin Arnold that takes one back to another time. Extracted from the Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, October 26, 1901 where it was republished from a source that is not indicated. (It does not seem to be available elsewhere on the internet.)

Here is however some beautiful prose by Sir Edwin Arnold that takes one back to another time. Extracted from the Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, October 26, 1901 where it was republished from a source that is not indicated. (It does not seem to be available elsewhere on the internet.)

Railway travel in India.

by Sir Edwin Arnold

Although constructively and mechanically so much the same everywhere, it is remarkable how greatly railways differ in different countries. For myself, I have always fancied that countries possess individual features-faces as special to themselves as those of men and women. I think if an Afrit of the Arabian Nights were to waft me asleep through the moonlight, like Bedreddin Hassan and to put me down in any part of India, Japan, Egypt, Africa - nay, even of Europe or America - I should know at a glance - by the general aspect of trees, fields, sky and landscape, let alone of the people and the birds and beasts- exactly where I had arrived.

So too, I think a close observer could always tell, if had travelled much, just where he was journeying by the look, the system, the style, the character, of his train and his railway carriage. He could know a Spanish train by its sluggishness; a Dutch train by the prevalence of pipes and tobacco; American trains by bell and cowcatcher; Egyptian trains by the dust and the dogs rushing on board for scraps; a Japanese train by its punctuality and disregard of comfort; a Russian train by its samovar, or tea-urn; and so on.

Indian trains are particularly sui generis, and for the benefit of English tourists who are contemplating a run through the wonderful Eastern Dominions of his Majesty King Edward I will her descant a little about travelling on Indian railway lines.

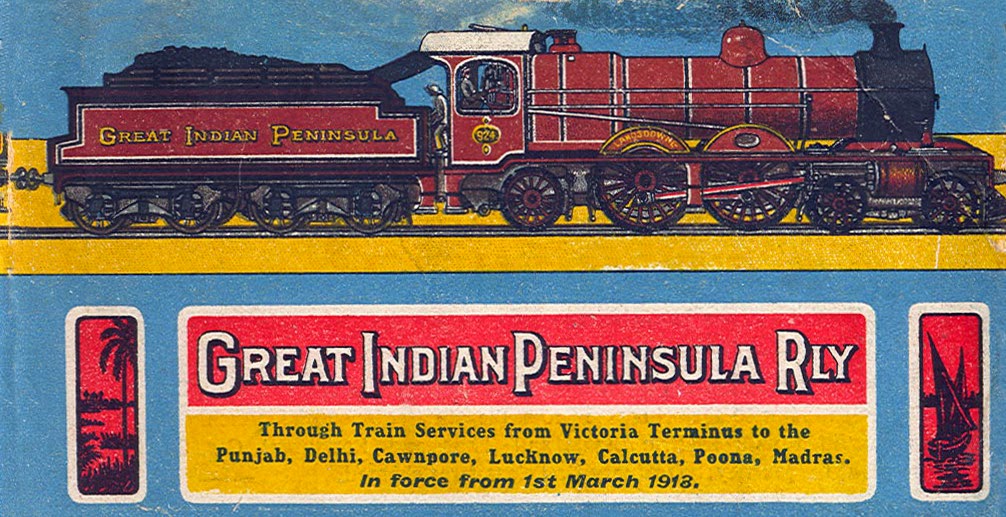

FIrst with regard to stations, you will not see anything finer or grander in that way, go where you will, than the Victoria Station, the Bombay terminus of the Great Indian Peninsular Railway. Suppose we take a run from there, the beautiful Gothic palace of traffic, rising stately and splendid between the picturesque vistas of the Esplanade Market and the Boree Bandar Road of Bombay. With its noble faced, rich sculpture, and high commanding dome, that edifice cost a million and a half dollars to build and yet, for all that superb appearance, there is not a more roomy or convenient station in the world.

One starts royally on a trip it must be confessed, from such a "gare," and nowhere else can one see a crowd so bright in colour, or varied in nationality, as will be hanging about the steps of the entrance, or filling its huge hall and waiting rooms. Western crowds are dull in general tint-grey and black and ant-like, except for what women do with hats and blouses and parasols to redeem them. But this throng about an Indian depot is a veritable moving bed of flowers, with the many-hued turbans of the men and the gladsome dyes of the saris and cholis worn by the girls and matrons. Even the lowest castes are dressed gorgeously as far as colour goes, and all have silver or glass ornaments, many, even, valuable gems in their earrings and nose-rings.

Those who are intending to make a serious journey betake themselves very early to the station, and sit down in family groups, with their modest belonging,s tied in cloths or packed in bamboo baskets, placed in their midst. They are wealthy in one thing only, that is time, which they value very little, and cheerfully waste in chatter, while circulating the hubble-bubble, or slowly chewing the pan-supari - that is, the betel-nut quid, the universal and perpetual solace of India, which is so peculiar to her peoples.

You will try it once, but never again- chips of the areca-nut are broken up by a sort of steel nut-cracker and mingled with a pinch of lime, all wrapped in a leaf of the pepper vine[sic], and fastened with a clove. Masticating this turns the saliva red, of which signs are only too ubiquitous, and the taste of the compound is astringent and aromatic; the thing itself being indispensable to the Indian natives, every one of whom in that station-hall will possess his supari-bag, with a supply for the long road.

The women, poor gentle souls, will have some chupatties-cakes-in a cloth, with a "hand" of bananas or a basket of mangoes, for the trip, and perhaps a water-jar. But in that land of thirst the arrangements for drinking on the journey are very carefully made by the management. At almost every station a man of the proper caste will go up and down the platform, shouting aloud "Pani! pani" and dispensing draughts to the thirsty, or filling up their golahs and chatties.

You yourself must also make preparations for an Indian railway run, of any length, of a kind which would never be thought of at home. First of all you must and will have engaged a good man-servant, a "boy," on whom you will vastly depend for comfort. you cannot do without him at hotel, dak, bungalow, or even in private houses; and if he cheats a little he will, if reasonably honest, limit the peculations of others. Obtain a good "boy," and pay him fairly; it is he who will buy the tickets and take the places.

Then the next thing is a good tiffin basket, which he will keep sedulously filled with potted meat, biscuits, wine, soda-water, etc., with doubtless the machinery to brew tea; an Etna, spirits of wine, and the like, for you must not trust unboiled water or milk in the land. Moreover, although some of the way-side stations have excellent restaurants, these do not always turn up on the route when the voyager needs them most.

Then, again, he must carry his own light bedding with him-two silk or cotton razais, well wadded, and a pillow. The guide-books justly counsel that there must be two razais. The ready-made ones are usually very thin, but they can be got to order of any thickness. To these should be added a pillow-case, calico sheets, and a blanket. A rough waterproof cover in which to wrap the bedding must not be omitted, or the first time the bedding is carried any distance by a coolie, or packed on a pony, it may be very much soiled. A water-proof sheet is a very valuable addition to the bedding.

Without such a modesty supply of covering as is here indicated, a traveller may at any time have to spend a night shivering in the cold, which would probably result in an attack of ague.

To his boy, his tiffin-basket, and his bedding the tourists will add a copy of the "Indian A.B.C. Guide," or the "Indian Bradshaw," and for the rest he may safely trust the companies. They do all they can for the well-being of travellers, and especially those of the first class. To quote the guide-book: "Every first and second class compartment is provided with a lavatory, and the seats, which are unusually deep, are so arranged as to form couches at night. There are refreshment rooms at frequent intervals, and some of them are very well managed and supplied. The station-masters are particularly civil and obliging, and, as a rule, are most useful to travellers in providing ponies, conveyances, or accommodation at out-of-the-way stations if notice be given them beforehand. They will also receive letters address to their care; this is often a convenience to travellers."

Of course, it must be in what is called the "cold weather" that you traverse the various lengths and breadths of Hindustan. From the middle of November to the middle of March is the ideal period. Yet even then, and always, the sun must be respected from 9 a.m. until 4 p.m, and many a burning hot hour at best will be passed in the railway carriage. This may be foreseen by the method in which the railway-stock has been constructed.

The first-class compartments will have a double roof to them, to soften the fierce impact of noonday sunshine, and the windows will be duplicated, with pale purple or green glass and "jilmil"-shutters-to exclude, as far as possible, the hot winds and the dust. On those lines, too, where tunnels do not forbid the arrangement, the Transatlantic tourist will be amused to behold the third and fourth class carriages, devoted to the traffic of the common people, fashioned in storeys, so that, as with the Chinese pork-express, there are layers of humble travellers berthed over the heads of others- a kind of rolling Noah's Ark in floors.

In this luxurious fashion will the Hindu, with his family, contentedly journey day and night and go upon pilgrimages, being easily satisfied if he can only get over the ground cheaply. It was a moot point, at the commencement of railway-making in India, whether or not that Shastras, the Holy Books, would permit orthodox and devout Hindus to perform pilgrimages by the aid of steam.

Happily for the dividends of shareholders and for the convenience of the native public the pundits decided that there was nothing recorded against such a practice in Ved or Smriti; and it is the swarm of simple people which nowadays makes the Indian lines pay, together, of course, with the trade in grain, cotton, and general produce.

Remember that one must not expect good hotels in India. There are at Bombay, Delhi, Benares, Calcutta, and Madras some that are fair and sufficing, but not to him who has been accustomed to the magnificent accommodation provided by London hostelries. Here and there the railway depot will have bedroom as well as a restaurant, but along all by-roads, and in the Mofussil generally, the dak bungalow is just a plain white-washed shelter, with a "charpoy," a bed-stead or two, plus the services of a Khansamah, and the chance of a very tough fowl, which is caught, amid wild confusion, at the moment of the arrival of the guest and takes a tardy but desperate revenge for his death by the indigestion it bequeaths to this destroyer.

In whatever direction your Indian train may be moving, the landscape on either side, even as seen through the rapidly shifting frames of the windows, will be new to the Western visitor. If he be at all a botanist, or should he have any companion with him who can name and explain the details of such leafy and flowery vistas as may be seen in Guzerat or the Concan and Deccan, those leagues of moving plain, jungle, and village would not pass without instruction and interest.

It adds immensely to the charm of any country when you understand a little of its flora and fauna. Along the Bombay lines it would go hard but that one might point out to him the white and golden star-flowers of the champak; the custard-apple, Sita's fruit; and the lotus, blue, rosy, or white, the flower par excellence of India, which has one hundred and thirty-five various names, and springs so pure and sweet from the black slime.

Then there will be the bil trees, and the neems with purple blossoms, and the bher- Zizyphus jujuba -which Mussulmans say is the Sidra, that grows in Paradise; together with the dark green mango (amba), and the gold mohur tree, and the bawa, the bloom of golden rain, and long pods like sword blades. There will be also countless acacias, babul, full of swinging weaver-birds' nests, and endless clumps of aloe and of prickly pear (nagphanna), as well as the classical kadamba and bright green karanda bushes; not to forget the banyan, the pipul, and palms of many kinds. One might see also the fragrant pandanus; the sandalwood (chandan); with everywhere bushes of erandi, the castor-oil plant, of which a Sanskrit verse says so contemptuosly:

"In the land where no wise men are, men of little wit are Lords.

And the castor-oil's a tree, when no tree else its shade affords."

If we could leave the train, and wander amid that dark deep thicket, there are many other strange plants and flowers which might be found, adding terror, or beauty, or marvel to those wild gardens of Asia. There is the deadly datura, with her flowers so milky-white and fragrant and her poison so quick; the samspan, which the little mongoose is believed to eat when the cobra has bitten him; and the charbaje, that opens her blooms exactly at four o'clock every afternoon, as punctual and almost as curious as the Desmodium gyrans, which twists and untwists her pink stem twice every twenty-four hours.

The tourist in India must not expect to see tigers and leopards, nor bears and bisons, from the windows of his carriage, but there will be something to interest any lover of nature all the same, and more, perhaps, than any other kind of swift travelling could supply. The sky will be full, especially near towns and stations, of kites and vultures, soaring aloft, and wheeling round and round with shrill cries. Over the pools and rivers he will mark the fish-tiger (muchi-bagh) hovering; a white and black halcyon and the pretty snow-white egrets will everywhere be noted stalking about among the grey cattle, and the king-crow flitting with his long black tail, and the jungle-dove with pearled and jewelled neck, cooing from every bush; as well as the green and bronze bee-eater hawking the butterflies, the "seven brown sisters" feeding and chattering in the bushes, and, perhaps, some grey thievish jackals stealing home at dawn.

There are many railways in the land along which he would be very likely to catch glimpses of the beautiful and graceful Indian antelopes, the black-buck, which are still plentiful in the central plains. I was riding myself once on a ballast-engine in the Deccan to get back more quickly to my educational duties, when we surprised a wolf in the entrance of a deep and long cutting, and never shall I forget how "Lupus" put on the pace as we rattled behind him between the steep embankments.

In passing through the green flats and forests of Guzerat, there are districts where for miles and miles you may beguile the journey by watching the monkeys, the bandar-log, those strange four-handed folk who come down to sit in the babul trees and to look at the passing trains and the travellers. Secure from all interference-for the white man must not molest them, and the brown man will not- they perch by families on the branches of the trees lining the track, and with their long tails swinging and their furry jaws busy with the fruit which they have stolen, like meditative Asia herself, they "let the legions thunder past." Or they squat demurely, in companies, about the fields of millet and grain, the old gossips together, and the youngsters merrily playing- all as confident and cool as if they were citizens of the place, and had votes.

In Rajpootana you may often notice, from the passing train, the beautiful dark blue peacocks break in a thunder of jewelled wings and lightning of purple plumes from the white marble rocks at the edge of the jungle, and you will pass many and many a spot notoriously frequented by tigers and panthers; no more visible, of course, on that account than if the wild green fastnesses concealed nothing except porcupines and mongoose.

The engineers along the various lines are mainly Europeans. There are not many Hindus or Mohammedans who have as yet the courage or the knowledge to drive the terrible and wonderful ag-gadi, the fire-horse, of which the Panjabi verse sings:

"Now is the devil-horse come to Sindh,Wah, wah, Guru! that is true.

His belly is stuffed with the fire and the wind."

In parts of India the wandering tribes will still be offering tributes to the flying locomotives, and even prostrating themselves before the telegraph wire, which they style "sheitan-ka-rashi," the "devil's string."

Most of the stationmasters are Bengali Babus or Deccani clerks, or else some other Hindus educated at the schools and colleges. Such quiet duties suit them well, and they are very attentive and sedulous, but strictly given to carry out to the letter their bye-laws, and to refer on all possible occasions for directions from their superiors. Thus it is really no myth, but a solemn fact, that once, on the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, the Chief Superintendent received at the central depot from a member of the staff of a minor station in the up-country this telegraphic message:"Tiger on the platform, has killed station-master; is now devouring tikkit-wallah, Please wire instruction"!

|

| "Tiger jumping about on platform, men will not work; please arrange." (Copy of telegram received at local office of the railway company) |

Further reading

- Albion, Robert Greenhalgh (1926) Forests and sea power. The Timber problem of the Royal Navy 1652-1862. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass., USA).

Postscript

- Some other railway ornithologists who collaborated with Hume include Henry Charles Edward Wenden (1841-1919) who worked in Poona [Wenden met with Edward Lear in 1874 along with H.P. Le Mesurier]

No comments:

Post a Comment